An explosive court filing from the Guantanamo Military Commission — a court considering the cases of defendants accused of carrying out the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York — has seemingly confirmed what many Americans have suspected for years.

At least two 9/11 hijackers had been recruited into a joint CIA-Saudi intelligence operation that was covered up at the highest level, according to the court filing.

The filing raises questions about the relationship between Alec Station, a CIA unit set up to track Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and his associates, and two 9/11 hijackers leading up to the attacks.

The original version, published via a Guantanamo Bay court docket, was entirely redacted. Independent researchers obtained an uncensored copy.

The filing is a 21-page declaration by Don Canestraro, a lead investigator for the Office of Military Commissions, the legal body overseeing the cases of 9/11 defendants. It summarizes classified government discovery disclosures, and private interviews Canestraro conducted with anonymous high-ranking CIA and FBI officials. Many agents who spoke to Canestraro headed up Operation Encore, the Bureau’s long-running investigation into Saudi government connections to the 9/11 attack.

Canestraro reportedly found that two of the 9/11 hijackers had been recruited either knowingly or unknowingly into a joint CIA-Saudi intelligence operation which may have gone awry.

Until March 2022, when a large number of FBI records were declassified at the White House’s request, those shocking details were kept from the public.

About the two pilots via Firstpost:

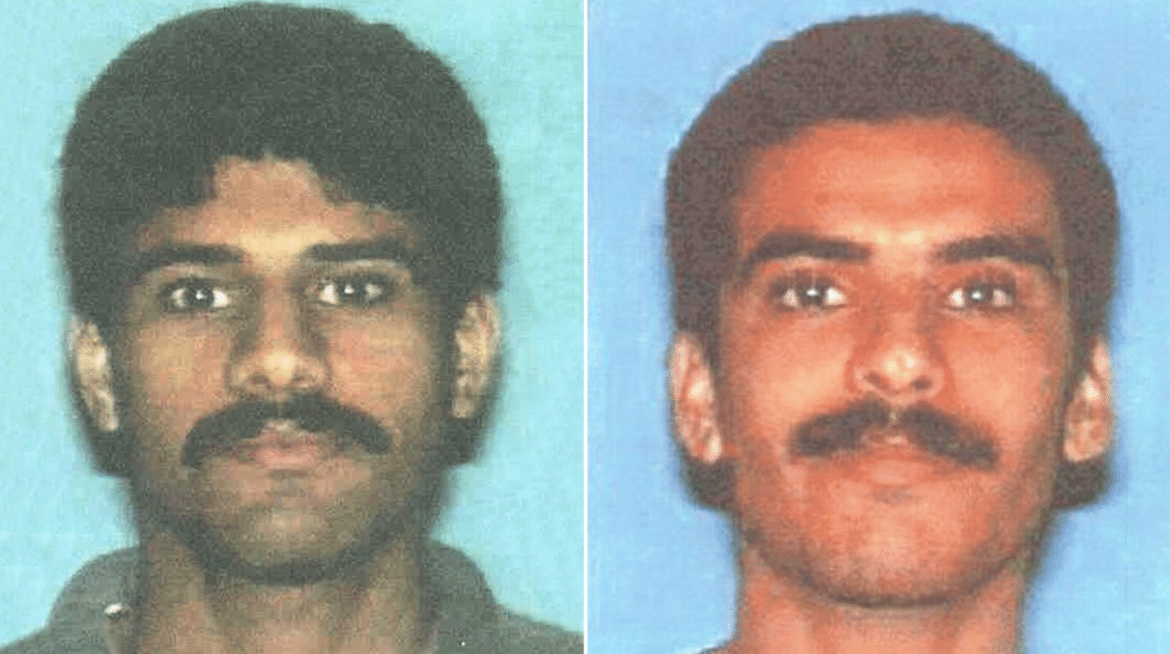

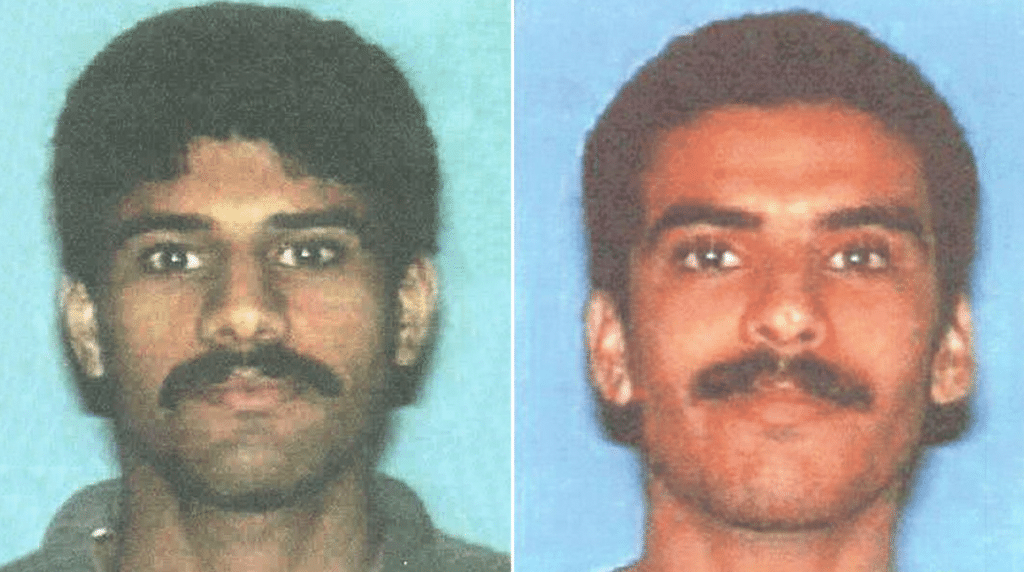

The two pilots

Activities of Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar in the 18 months preceding the day of 9/11 attacks are one of the numerous persistent mysteries that have not yet been fully clarified more than 20 years later.

Despite being repeatedly recognised by the CIA and NSA as potential Al Qaeda terrorists prior to their arrival into the US in January 2000, the pair entered the country on multiple-entry visas, documents revealed.

They attended an Al Qaeda gathering in Kuala Lumpur just days prior to their arrival, where important decisions regarding the 9/11 attacks are thought to have been made.

The CIA’s Alec Station, a special unit set up to follow Osama bin Laden, requested that Malaysian authorities discreetly picture and record the meeting. Oddly, no audio was recorded.

However, this information should have been enough to deter Hazmi and Midhar from entering the US, or at the very least, to alert the FBI to their presence.

As it transpired, the CIA prevented Bureau representatives in Alec Station from informing their superiors about their admission for a six-month period without incident at Los Angeles International airport.

The documents reveal that one officer named Mark Rossini, who was then a member of Alec Station tried to warn FBI about the two men and the fact that they had multiple entry visa to the US.

“We’ve got to tell the Bureau about this. These guys clearly are bad. One of them, at least, has a multiple-entry visa to the US. We’ve got to tell the FBI,” Mark recalled discussing with his colleagues. “[But the CIA] said to me, ‘No, it’s not the FBI’s case, not the FBI’s jurisdiction.’”

As soon as they arrived, Omar al-Bayoumi, a Saudi national who lives in California, was contacted by Hazmi and Midhar in an airport café.

He co-signed their lease, paid them $1,500 towards their rent, helped them find an apartment in San Diego over the course of the following two weeks, and introduced them to Anwar al-Awlaki, an imam at a nearby mosque.

In 2011, a US drone strike in Yemen resulted in the death of Al-Awlaki.

After 9/11, Operation Encore, an FBI investigation into possible Saudi participation in the attacks, naturally turned its attention to Bayoumi.

He explained that he met Hazmi and Midhar by accident in a 2003 interview with Riyadh-based investigators. He said he overheard them speaking Arabic, realised they couldn’t speak English, and decided to help them out of kindness.

The Bureau came to a quite different conclusion: Bayoumi was a Saudi intelligence agent and a component of a larger militant Wahhabist network operating in the US that dealt with a wide range of potential and real terrorists and kept tabs on anti-Riyadh dissidents’ overseas activities.

Additionally, both the Saudi government and Encore believed there was a 50/50 possibility he knew of the 9/11 attacks before they occurred.

The recently made public Guantanamo Military Commission document provides additional insight about Bayoumi’s interactions with Hazmi and Midhar, the CIA’s intense interest in them, their activities during their stay in the US, and their failure to inform the FBI of their presence until late August 2001.

The content strongly implies that the CIA hindered official investigations to hide its infiltration of Al Qaeda based on an examination of classified information maintained by the FBI and Pentagon, as well as interviews with representatives of both agencies.

About Alec Station from The GRAYZONE:

A most ‘unusual’ CIA unit

Alec Station’s formal remit was to track bin Laden, “collect intelligence on him, run operations against him, disrupt his finances, and warn policymakers about his activities and intentions.” These activities would naturally entail enlisting informants within Al Qaeda.

Nonetheless, as several high level sources told Canestraro, it was extremely “unusual” for such an entity to be involved in gathering intelligence and recruiting assets. The US-based unit was run by CIA analysts, who do not typically manage human assets. Legally, that work is the exclusive preserve of case officers “trained in covert operations” and based overseas.

“CS-10”, a CIA case officer within Alec Station, concurred with the proposition that Hazmi and Mihdhar enjoyed a relationship with the CIA through Bayoumi, and was baffled that the unit was tasked with attempting to penetrate Al Qaeda in the first place. They felt it “would be nearly impossible…to develop informants inside” the group, given the “virtual” station was based in a Langley basement, “several thousand miles from the countries where Al Qaeda was suspected of operating.”

“CS-10” further testified that they “observed other unusual activities” at Alec Station. Analysts within the unit “would direct operations to case officers in the field by sending the officers cables instructing them to do a specific tasking,” which was “a violation of CIA procedures.” Analysts “normally lacked the authority to direct a case officer to do anything.”

“CS-11”, a CIA operations specialist posted to Alec Station “sometime prior to the 9/11 attacks” said they likewise “observed activity that appeared to be outside normal CIA procedures.” Analysts within the unit “mostly stuck to themselves and did not interact frequently” with others. When communicating with one another through internal cables, they also used operational pseudonyms, which “CS-11” described as peculiar, as they were not working undercover, “and their employment with the CIA was not classified information.”

The unit’s unusual operational culture may explain some of the stranger decisions made during this period vis a vis Al Qaeda informants. In early 1998, while on a CIA mission to penetrate London’s Islamist scene, a joint FBI-CIA informant named Aukai Collins received a stunning offer: bin Laden himself wanted him to go to Afghanistan so they could meet.

Collins relayed the request to his superiors. While the FBI was in favor of infiltrating Al Qaeda’s base, his CIA handler nixed the idea, saying, “there was no way the US would approve an American operative going undercover into Bin Laden’s camps.”

Similarly, in June 2001, CIA and FBI analysts from Alec Station met with senior Bureau officials, including representatives of its own Al Qaeda unit. The CIA shared three photos of individuals who attended the Kuala Lumpur meeting 18 months earlier, including Hazmi and Mihdhar. However, as an FBI counter-terror officer codenamed “CS-15” recalled, the dates of the photos and key details about the figures they depicted were not revealed. Instead, the analysts simply asked if the FBI “knew the identities of the individuals in the photos.”

Another FBI official present, “CS-12”, offers an even more damning account. The Alec Station analysts not only failed to offer biographical information, but falsely implied one of the individuals might be Fahd Al-Quso, a suspect in the bombing of the USS Cole. What’s more, they outright refused to answer any questions related to the photographs. Nonetheless, it was confirmed that no system was in place to alert the FBI if any of the three entered the US – a “standard investigative technique” for terror suspects.

Given Hazmi and Mihdhar appeared to be simultaneously working for Alec Station in some capacity, the June 2001 meeting may well have been a dangle. No intelligence value could be extracted from inquiring whether the Bureau knew who their assets were, apart from ascertaining if the FBI’s counter-terror team was aware of their identities, physical appearances, and presence in the US.

About the cover-up from Florida Bulldog:

While most criticism in the declaration is directed at the CIA, higher ups at the FBI were also targets of the FBI agents’ complaints.

An ex-agent in the bureau’s Washington Field Office referred to as CS-9, was part of a squad tasked with investigating leads developed after the attacks. CS-9 told Canestraro that “agents were told they were not permitted to interview Saudi nationals in support of their investigation. CS-9 stated that many of the leads developed during his/her investigation pointed toward the Saudi diplomats stationed in Washington, D.C.

Another former FBI agent, CS-4, who in the spring of 2002 supervised two other FBI agents assigned to the CIA’s UBL Station, stated that “CS-3 approached him/her and said, ‘Boss, something is bothering me big time…we [meaning the United States government] could have prevented the 9/11 attacks.” CS-3 then outlined the CIA intelligence that showed Hazmi and Mihdhar had attended the Malaysian al Qaeda meeting, that the CIA knew in January 2001 that both men had multiple entry visas to the U.S. and that his FBI colleague had written a report on the future hijackers that “was not distributed on orders from one of the analysts at UBL Station.”

CS-3 gave his supervisor a draft of the report. The supervisor, a male, asked who else knew about it. CS-3 said just him and the colleague who wrote it. The supervisor said he then contacted FBI deputy director for counterterrorism Pasquale D’Amuro saying he needed to meet right away. The supervisor hopped in his car and “at a high rate of speed” drove to FBI headquarters where he met with D’Amuro and gave him the secret UBL report on Hazmi and Mihdhar.

“D’Amuro read the cable then told CS-4, ‘I will take care of this,’ the declaration says. “CS-4 noted that D’Amuro never mentioned the cable’s existence” again.

A short time later, though, CS-4 was promoted out of UBL Station to a senior liaison position outside of the FBI. He hadn’t asked for a promotion and told Canestraro he felt he was moved away from UBL Station because he “knew about the existence” of the CIA’s secret report on Hazmi and Mihdhar. CS-4 added he believed he was moved to ensure he “kept silent.”

Ex-FBI agent CS-23 said that when the FBI became aware of Omar Bayoumi’s affiliation with Saudi Intelligence and the CIA’s recruitment operation through Bayoumi after 9/11, “senior FBI officials suppressed investigations into the above. CS-23 also told me that FBI agents testifying before (Congress’s) Joint Inquiry into the 9/11 attacks were instructed not to reveal the full extent of Saudi involvement with Al-Qaeda,” Canestraro’s declaration says.

The declaration does not say who ordered FBI field agents investigating 9/11 not to interview Saudi nationals or other agents to lie to Congress – or why.